“YOU ARE NEVER INVISIBLE,” 2022. Vinyl on acrylic panel, 48 x 48 inches. Photo by Flying Studio, courtesy of David Kordansky Gallery

Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley works in the mediums of animation, sound, performance, and video game development. Their practice focuses on intertwining lived experience with fiction to imaginatively retell the stories of Black trans people.

Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley is from London and based in Berlin. Brittany Richmond is from Los Angeles and based in Savannah. Both Brathwaite-Shirley and Richmond were born in the early 90s. This interview was transcribed from texts and voice notes exchanged over WhatsApp, and has been edited for brevity.

Brittany Richmond: I first came across your work online, rather than in person at a gallery or museum, and right off the bat I was very intrigued that a lot of your work is actually intended to be viewed online. I’m thinking specifically about your work “Black Trans Archive” [https://blacktransarchive.com/], which I feel is really important to talk about in order to understand everything that you make. Can you explain what this work is? What does archiving mean to you? And how do you do it? How did it become part of your practice?

Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley: I think the Internet is one of the most underutilized mediums currently still, and I think it's also not a respected medium to use. I think people often think of it as a place to put work rather than a medium itself, to make work and for work to exist. We saw that definitely during COVID time about how people really struggle to adapt their work online because they were adapting it rather than respecting the medium of the Internet. I say the Internet because every corner and the way you use it, and the code base of what you're using shifts the medium of what you're making... If it's not made for online it's very difficult to adapt, it’s like adapting a sculpture to a painting. It's a different artwork altogether. You can't expect it to do the same things, as it's existing completely differently.

I noticed that when I was in uni and I was researching a lot about Black trans archiving and where the hell Black trans people were and I wasn't seeing any. I wanted to make this archive myself. And so I made this archive called Black Trans Archive, which was the first art commission I got after university. It was essentially a work made alongside, I think 10 to 12 different Black trans people, to try and archive them, so that we'd have a marker for the future and archive them in a way that was our own way. Something that I have found very disturbing about archives is that they were so inaccessible, they were never really made for us. They felt like they were only made for those in an academic sphere. They made little to no sense unless you knew exactly what you were looking for. I wanted an archive to do more than that and to be used more than that. And so that's how the Black Trans Archive started to exist. The dot com series, which is what I call it, is all the work I’ve made online. And then COVID happened. I already had this online practice and I already had planned this remake of another game, I said, okay, I make all these online games and it's just become something that I hugely respect as a genre of art. I think some of the most amazing pieces I've ever seen are called ARGs, Augmented Reality Games – they use the Internet and respect the Internet as a medium – It's very important to approach the medium you are using as a medium and not a means to an end.

Installation image from GET HOME SAFE by Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley at the SCAD Museum of Art, 2023. Photo courtesy of Savannah College of Art and Design

For me archiving is about trying to capture the soul of an individual. It's trying to capture an essence. It's not just about all the facts, although that's important, too, but it's about making sure that person is represented in some way for future generations to look back and see that person so that maybe they can draw a line between themselves and that individual or to learn something about them. The way I archive is not just about rendering a realistic representation of them, it's more about diving in and trying to understand how an entire space can be made for an individual, and record them from the foundation of that space to the very words of the person and the identity that they have. So it's about, for me, layering, and the ways in which I do it are often by speaking to the person first, understanding and giving, kind of acting a bit like a translator, a digital translator… I am more listening to what they're saying, I'm just mediating the conversation. And then when they have given me all the information and photos to use, anything they really want, then I try and become a director and figure out how a world would be made around these particular things that they've given me.

BR: The exhibition that we worked on together at SCAD MOA, “GET HOME SAFE,” invites visitors to interact with an immersive installation of virtual, digital, and physical works that are a part of your efforts to archive Black trans voices, bodies, and lived experiences. The core of the exhibition is a work that takes the form of a video game that you designed, and it is inspired by the history and aesthetics of early online role-playing games, also known as MMORPGS. How did you get into video games? What led you to work in this format? Can you give us an example of the MMORPGs that inspired you?

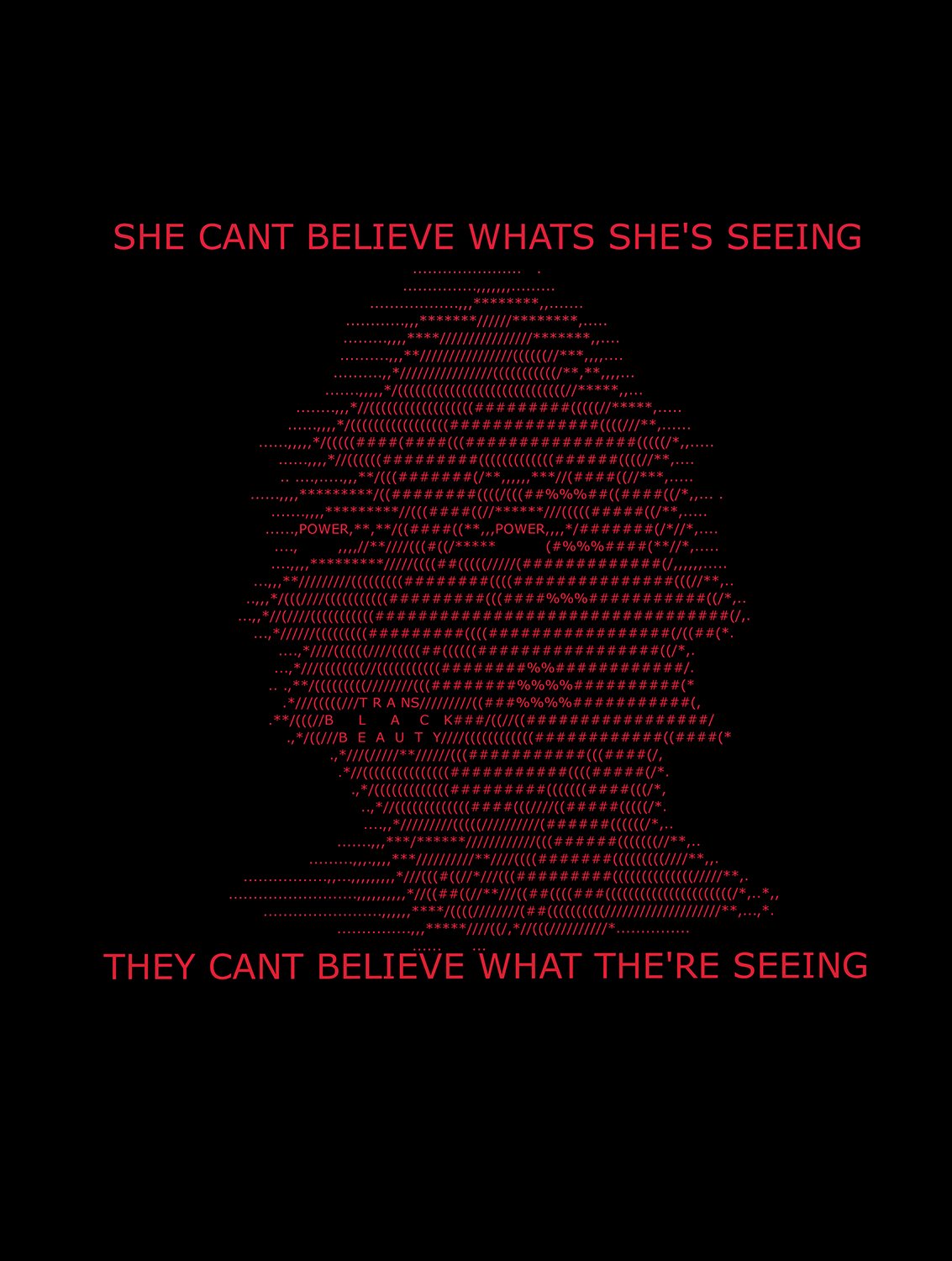

Screenshot from The Black Trans Archive, www.blacktransarchive.com

DBS: I actually got into video games through my dad. I think the first video game I played was Road Rash for the Sega Mega drive. There was one game that blew me away at the time, which was Star Wars Rebel Assault II, which put together polygons, videos, and digitized sprites – which essentially means pictures of people as like sprites in games. Everything looked so real to me. At the time, I was young enough to think that in movies, when people died, they actually died, and in games when you saw a representation of someone, it was like a soul. Part of the soul was there and you were playing that particular part of the soul, and so that stayed with me forever. I remember distinctly one of the games that I started to think about making my own version of was actually Doom. I had Doom on the Game Boy Advance, and I would always think about what it would be like to change all the sprites and build my own levels and tell stories through that engine. I always wanted to work in this format, I was so drawn to it. There was something about it, something about creating a world and filming within that world and bringing it to life that I always wanted to do. The idea that people could participate in what's going on, and for the game to react to who they were, how they played, and how they treated the world, and what choices they made, really lit a fire underneath me. There was a particular comment when I used to make these films that would have game elements in them, like an inventory screen or choices that would pop up, but it's all part of a film, so you wouldn't have any ability to change it: someone told me that they liked my work because they could watch it and ignore the reason it was made, because they just liked the visuals. That's when I realized I have to make games and I have to not only make games but make work that actually challenges how people enter galleries and how people look at work.

Courtesy of the artist

BR: After zoom meetings and phone calls, we first met in person in New York at a screening series of your animation films at MoMA. There I learned that your animated films are often precursors to your video games. It made me think about how there is so much that goes into making a video game!! To me, video games are the 21st century version of a gesamtkunstwerk “total work of art” – to make one you have to create a full realm: the visuals, the audio, the landscape, the characters, and also think about the player and the narratives – how do you do all that? What’s your process for world-building and can you describe all the elements that go into it?

DBS: I use these game engines as diaries. I have this dream of approaching it like a game studio and doing the storyboards, and then building up to it and writing it, and doing it all like this – but it's never as smooth or as clean. For me, it often becomes quite messy and certain things feel like they just have to come at certain moments. And just like a diary, when you’re mad, you want to write something mad, I want to make something mad. When I'm sad, I want to make something sad. It's exactly like this. So often they start one way and they take on their own direction completely. I feel like they kind of run me. I feel like they begin to tell me what to do. There's always a point where I hate the game – and that’s the moment that the game says this is what you’re making and you have to finish me. It takes a long time to get there. I feel it's not automatic. You don't know exactly what you're doing, and it's very confusing especially when you are trying to introduce game logic, actual choices, and make it link to why you're wanting to make the work in the first place and what you want to make people feel. It's very hard to juggle all this, especially when you know there's a bunch of different identities that will be seeing the work and the work is made for Black trans people, and how do I maintain that space, as well as leaving room for others to also engage with it and feel something from it. The work is never supposed to be educational – it's supposed to be revealing for yourself. I often say that the audience is my main medium, and so I want the audience to be able to feel moved in a way, and to paint the gallery themselves by their actions. This is the way I'm thinking about it most of the time, and this is the way I'm kind of world building. If I'm archiving someone, it's a very different process because it begins a lot with listening and that begins a lot with trying to understand exactly who they are, what part of them I may be able to archive in the time we have, and how to build a world around what they told me. And it usually starts with images of them that I use as the text of the world, and then it goes from images to a model of them – then it goes from the model of them to the story around them – then it goes from the story around them to the voice of them. So, very bottom up. However, when I'm doing it from myself as an idea within myself, it's often splashed out.

Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley, Photo by Dan Weill Photography

BR: In the GET HOME SAFE video game, the player navigates a simulation of walking home at night within a world built from the fears and memories of those in our society who struggle to get home safely. Can you tell me more specifically about the world in the GET HOME SAFE video game? Is it the world we live in or is it a fantasy world?

DBS: Okay, if I’m to draw some real wild parallel lines here, often, I think that people see my existence as a kind of fantasy, a fetish or fad or a phase. So I kind of don't like the question. Is it real? Yeah, It's based on me going home and getting harassed. It's essentially my diary of this. That's what the work is about. It's my diary of harassment, especially down on one particular road in Berlin and what I used to do to cope with getting home. I'd make these songs, would sing these songs to be sad or to feel safer. I don't know if they work, but a lot of the music came from this. The music and the writing and the idea, everything came from a kind of distraction for me. I think it's one of the games I made for pretty much myself. Usually I'm trying to archive a lot of the work in the show, archiving people and on the wall, and I did have conversations, but I would say the work is a lot more of a diary. I don't know if I was in danger because nothing ever did happen. But over time I have a way of coping, essentially. So I use this game as a way of coping with this one specific thing, which is being followed home by these cars in Berlin, many, many times, and I'm being accosted on this one particular road in midtown in the center of Berlin, more times than I can count… So is it fantasy? I mean, sure, like every book and every story. It's a fantasy, but there's something really in it based on something that happened. I prefer to make a world out of the experience so that there is more there than just a focus on something that would be seen as maybe, like, traumatic or painful.

From Left: “GIVE IT BACK,” 2022. Vinyl on acrylic panel, 48 x 48 inches. “MIRROR SPEAKS,” 2022. Vinyl on acrylic panel, 48 x 48 inches. Photos by Flying Studio, Images courtesy of David Kordansky Gallery

BR: How did you extend the world you’ve built inside the GET HOME SAFE game into the installation at the museum?

DBS: I do something often which gets the most pushback, which is Terms and Conditions. I think it's really important that you set the environment of a space, and sometimes the environment itself, especially when it's in the context of a museum and people enter that environment with references, with their own frame of mind and carry that throughout the space. Sometimes I think it's really great to have a palate cleanser at the beginning to set them up for the space – it adds more weight to the space before you even step foot in there. It gives this moment of anxiety or anticipation or of worry or, you kind of question the words that are being used. But just that questioning gets you in the frame of mind, of questioning and looking in and thinking to yourself, Should I be here? Or Is this for me?... And so these Terms and Conditions I've done for pretty much every installation, it's one of the most important things I do and gets the most pushback. So clearly it's doing something from the institution. And so the world kind of then gets extended from that... You don't try and build the game in the real world. You try and build a space that houses and feels like it's tailored for a world that could hold the game. I'm often thinking of it like city building. So if you're trying to design a city for a group, a particular group of people, how do you build it? I make work about trans people. So if this is a Black trans space, how do I want to construct it so that it would have that foundation present within the install? The idea is that the environment should hold just as much lore and weight as the game itself.

Terms & Conditions, from GET HOME SAFE on display at SCAD MOA, 2023. Courtesy of Savannah College of Art and Design

BR: You have mentioned that interactivity is a key element in the work. Could you elaborate on that?

DBS: The whole point of making work like this is that the audience can’t come in as a consumer. They must come in as someone that has to activate the work. The work has to be activated by them. It's about taking part in all these things that we talk about, all these political points, all the things we stand on, all the reasons that we do things. I want to affect the way people live. I want people to change how they're living, I want people to think about the decisions they've made to get to this point, I hope the work does this to some extent. I want the work to be almost like a mirror for you to see or try out small parts of yourself.

BR: I really appreciate your responses. Thank you so much.

DBS: THANKK YOUUUU

Visit The Black Trans Archive at: www.blacktransarchive.com

###